It seems as though we must use sometimes the one theory and sometimes the other, while at times we may use either. We are faced with a new kind of difficulty. We have two contradictory pictures of reality; separately neither of them fully explains the phenomena of light, but together they do.Through the work of Max Planck, Albert Einstein, Louis de Broglie, Arthur Compton, Niels Bohr, and many others, current scientific theory holds that all particles exhibit a wave nature and vice versa.[2] This phenomenon has been verified not only for elementary particles, but also for compound particles like atoms and even molecules. For macroscopic particles, because of their extremely short wavelengths, wave properties usually cannot be detected.[3]

Although the use of the wave-particle duality has worked well in physics, the meaning or interpretation has not been satisfactorily resolved; see Interpretations of quantum mechanics.

Bohr regarded the "duality paradox" as a fundamental or metaphysical fact of nature. A given kind of quantum object will exhibit sometimes wave, sometimes particle, character, in respectively different physical settings. He saw such duality as one aspect of the concept of complementarity.[4] Bohr regarded renunciation of the cause-effect relation, or complementarity, of the space-time picture, as essential to the quantum mechanical account.[5]

Werner Heisenberg considered the question further. He saw the duality as present for all quantic entities, but not quite in the usual quantum mechanical account considered by Bohr. He saw it in what is called second quantization, which generates an entirely new concept of fields that exist in ordinary space-time, causality still being visualizable. Classical field values (e.g. the electric and magnetic field strengths of Maxwell) are replaced by an entirely new kind of field value, as considered in quantum field theory. Turning the reasoning around, ordinary quantum mechanics can be deduced as a specialized consequence of quantum field theory.

Classical particle and wave theories of light

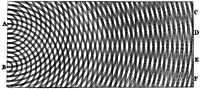

Thomas Young's sketch of two-slit diffraction of waves, 1803

James Clerk Maxwell discovered that he could apply his previously discovered Maxwell's equations, along with a slight modification to describe self-propagating waves of oscillating electric and magnetic fields. It quickly became apparent that visible light, ultraviolet light, and infrared light were all electromagnetic waves of differing frequency.

- Animation showing the wave-particle duality with a double-slit experiment and effect of an observer. Increase size to see explanations in the video itself. See also a quiz based on this animation.

Particle impacts make visible the interference pattern of waves.

Particle impacts make visible the interference pattern of waves.

A quantum particle is represented by a wave packet.

A quantum particle is represented by a wave packet.

Interference of a quantum particle with itself.

Interference of a quantum particle with itself.

0 Comments