Wormholes are consistent with the general theory of relativity, but whether wormholes actually exist remains to be seen. Many scientists postulate wormholes are merely a projection of the 4th dimension, analogous to how a 2D being could experience only part of a 3D object.[1]

A wormhole could connect extremely long distances such as a billion light years or more, short distances such as a few meters, different universes, or different points in time.

Visualization

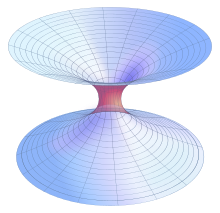

Wormhole visualized in 2D

Another way to imagine wormholes is to take a sheet of paper and draw two somewhat distant points on one side of the paper. The sheet of paper represents a plane in the spacetime continuum, and the two points represent a distance to be traveled, however theoretically a wormhole could connect these two points by folding that plane so the points are touching. In this way it would be much easier to traverse the distance since the two points are now touching.

Development

"Embedding diagram" of a Schwarzschild wormhole

Schwarzschild wormholes

The first type of wormhole solution discovered was the Schwarzschild wormhole, which would be present in the Schwarzschild metric describing an eternal black hole, but it was found that it would collapse too quickly for anything to cross from one end to the other. Wormholes that could be crossed in both directions, known as traversable wormholes, would be possible only if exotic matter with negative energy density could be used to stabilize them.[8]Einstein–Rosen bridges

Schwarzschild wormholes, also known as Einstein–Rosen bridges[9] (named after Albert Einstein and Nathan Rosen),[10] are connections between areas of space that can be modeled as vacuum solutions to the Einstein field equations, and that are now understood to be intrinsic parts of the maximally extended version of the Schwarzschild metric describing an eternal black hole with no charge and no rotation. Here, "maximally extended" refers to the idea that the spacetime should not have any "edges": it should be possible to continue this path arbitrarily far into the particle's future or past for any possible trajectory of a free-falling particle (following a geodesic in the spacetime).In order to satisfy this requirement, it turns out that in addition to the black hole interior region that particles enter when they fall through the event horizon from the outside, there must be a separate white hole interior region that allows us to extrapolate the trajectories of particles that an outside observer sees rising up away from the event horizon. And just as there are two separate interior regions of the maximally extended spacetime, there are also two separate exterior regions, sometimes called two different "universes", with the second universe allowing us to extrapolate some possible particle trajectories in the two interior regions. This means that the interior black hole region can contain a mix of particles that fell in from either universe (and thus an observer who fell in from one universe might be able to see light that fell in from the other one), and likewise particles from the interior white hole region can escape into either universe. All four regions can be seen in a spacetime diagram that uses Kruskal–Szekeres coordinates.

In this spacetime, it is possible to come up with coordinate systems such that if a hypersurface of constant time (a set of points that all have the same time coordinate, such that every point on the surface has a space-like separation, giving what is called a 'space-like surface') is picked and an "embedding diagram" drawn depicting the curvature of space at that time, the embedding diagram will look like a tube connecting the two exterior regions, known as an "Einstein–Rosen bridge". Note that the Schwarzschild metric describes an idealized black hole that exists eternally from the perspective of external observers; a more realistic black hole that forms at some particular time from a collapsing star would require a different metric. When the infalling stellar matter is added to a diagram of a black hole's history, it removes the part of the diagram corresponding to the white hole interior region, along with the part of the diagram corresponding to the other universe.[11]

The Einstein–Rosen bridge was discovered by Ludwig Flamm in 1916,[12] a few months after Schwarzschild published his solution, and was rediscovered by Albert Einstein and his colleague Nathan Rosen, who published their result in 1935.[10][13] However, in 1962, John Archibald Wheeler and Robert W. Fuller published a paper[14] showing that this type of wormhole is unstable if it connects two parts of the same universe, and that it will pinch off too quickly for light (or any particle moving slower than light) that falls in from one exterior region to make it to the other exterior region.

According to general relativity, the gravitational collapse of a sufficiently compact mass forms a singular Schwarzschild black hole. In the Einstein–Cartan–Sciama–Kibble theory of gravity, however, it forms a regular Einstein–Rosen bridge. This theory extends general relativity by removing a constraint of the symmetry of the affine connection and regarding its antisymmetric part, the torsion tensor, as a dynamical variable. Torsion naturally accounts for the quantum-mechanical, intrinsic angular momentum (spin) of matter. The minimal coupling between torsion and Dirac spinors generates a repulsive spin–spin interaction that is significant in fermionic matter at extremely high densities. Such an interaction prevents the formation of a gravitational singularity.[clarification needed] Instead, the collapsing matter reaches an enormous but finite density and rebounds, forming the other side of the bridge.[15]

Although Schwarzschild wormholes are not traversable in both directions, their existence inspired Kip Thorne to imagine traversable wormholes created by holding the "throat" of a Schwarzschild wormhole open with exotic matter (material that has negative mass/energy).

Other non-traversable wormholes include Lorentzian wormholes (first proposed by John Archibald Wheeler in 1957), wormholes creating a spacetime foam in a general relativistic spacetime manifold depicted by a Lorentzian manifold,[16] and Euclidean wormholes (named after Euclidean manifold, a structure of Riemannian manifold).[17]

Traversable wormholes

The Casimir effect shows that quantum field theory allows the energy density in certain regions of space to be negative relative to the ordinary matter vacuum energy, and it has been shown theoretically that quantum field theory allows states where energy can be arbitrarily negative at a given point.[18] Many physicists, such as Stephen Hawking,[19] Kip Thorne,[20] and others,[21][22][23] argued that such effects might make it possible to stabilize a traversable wormhole.[24][25] The only known natural process that is theoretically predicted to form a wormhole in the context of general relativity and quantum mechanics was put forth by Leonard Susskind in his ER=EPR conjecture. The quantum foam hypothesis is sometimes used to suggest that tiny wormholes might appear and disappear spontaneously at the Planck scale,[26]:494–496[27] and stable versions of such wormholes have been suggested as dark matter candidates.[28][29] It has also been proposed that, if a tiny wormhole held open by a negative mass cosmic string had appeared around the time of the Big Bang, it could have been inflated to macroscopic size by cosmic inflation.[30]

Image of a simulated traversable wormhole that connects the square in front of the physical institutes of University of Tübingen with the sand dunes near Boulogne sur Mer in the north of France. The image is calculated with 4D raytracing in a Morris–Thorne wormhole metric, but the gravitational effects on the wavelength of light have not been simulated.[note 1]

Wormholes connect two points in spacetime, which means that they would in principle allow travel in time, as well as in space. In 1988, Morris, Thorne and Yurtsever worked out how to convert a wormhole traversing space into one traversing time by accelerating one of its two mouths.[20] However, according to general relativity, it would not be possible to use a wormhole to travel back to a time earlier than when the wormhole was first converted into a time "machine". Until this time it could not have been noticed or have been used.[26]:504

Raychaudhuri's theorem and exotic matter

To see why exotic matter is required, consider an incoming light front traveling along geodesics, which then crosses the wormhole and re-expands on the other side. The expansion goes from negative to positive. As the wormhole neck is of finite size, we would not expect caustics to develop, at least within the vicinity of the neck. According to the optical Raychaudhuri's theorem, this requires a violation of the averaged null energy condition. Quantum effects such as the Casimir effect cannot violate the averaged null energy condition in any neighborhood of space with zero curvature,[34] but calculations in semiclassical gravity suggest that quantum effects may be able to violate this condition in curved spacetime.[35] Although it was hoped recently that quantum effects could not violate an achronal version of the averaged null energy condition,[36] violations have nevertheless been found,[37] so it remains an open possibility that quantum effects might be used to support a wormhole.Modified general relativity

In some hypotheses where general relativity is modified, it is possible to have a wormhole that does not collapse without having to resort to exotic matter. For example, this is possible with R2 gravity, a form of f(R) gravity.[38]Faster-than-light travel

Wormhole travel as envisioned by Les Bossinas for NASA

0 Comments